by Renee Ghert-Zand, J. Correspondent | J Weekly |

When Charlotte Smith reads from the Torah at her bat mitzvah next month, she will be “holding history,” she says.

The sefer Torah that Charlotte will hold and read from June 29 in front of her friends and family at the Smith-Madrone Winery in Napa Valley is a very special one for her family. The sacred scroll survived the Holocaust and traveled over two continents and an ocean to be read from, 75 years later, by the great-great-granddaughter of the man who safeguarded it from the Nazis.

Unbeknown to Charlotte’s family, the Torah has been in Marin for the past several decades. It was only through a combination of serendipity and amateur sleuthing on the part of Charlotte’s mother (and Hamburger’s great-granddaughter) Julie Ann Kodmur that the St. Helena family discovered the scroll’s nearby whereabouts.

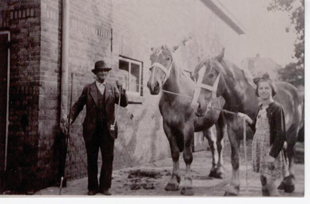

The Hamburger Torah derives its name from David Hamburger, who kept it at home in the small town of Fürstenau in the northwest corner of Germany. Hamburger was the de facto head of the town’s small Jewish community, and its members would gather in his house for religious services. A horse and cattle trader, Hamburger used to like to sit in his garden and tell Torah stories to his children Bette, Ruth and Siegfried; his wife died in the Spanish flu epidemic in 1918.

Siegfried managed to immigrate to San Francisco in 1938, as did Ruth with her husband and young daughter. Bette married a Dutch Jew and moved to Holland. Bette, her husband and their twin daughter and son died at Auschwitz.

David Hamburger remained in Fürstenau and was hidden overnight on Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938 by friends at the local Catholic hospital. The next day, he made it out of Germany to Holland by train. He took a portrait of his wife and the Torah with him.

While his wife’s portrait did not survive the war, both Hamburger and the Torah emerged intact after being hidden for eight years by various farmers and priests in the Dutch countryside. Hamburger, who remarried after the war, chose to remain in Holland, and the Torah stayed with him.

It was stored in Hamburger’s home until he was killed at the age of 75, when a truck hit his motorcycle. When Siegfried came to take care of his father’s effects, he brought the Torah with him to the Bay Area. It remained with Siegfried until he passed it on to his son Steven.

Steven, in turn, gave the Torah to Rabbi Jerry Winston for use at his small San Anselmo congregation, Barah. That was the last the family knew of the scroll’s whereabouts.

Kodmur also knew Winston, who “married my husband and me in 1996, and somehow it came up in conversation that he had also married my cousin Steven Hamburger a number of years earlier,” she recalled. “But I am pretty sure that the Torah was not mentioned.” She last saw Winston at Charlotte’s baby naming, and thoughts of the Torah took a back seat for the next 12 years.

As Charlotte began nearing Jewish adulthood, the Torah once again entered Kodmur’s consciousness. “It was in the recesses of my mind,” she said. “It’s a ritual object to which I and my family have an intense connection.”

She started asking around at North Bay synagogues whether anyone had knowledge of the Hamburger Torah. Eventually, she got a call from a woman, a friend of Winston’s, who told her that the rabbi’s sons had given the Torah to Rabbi Alan Levinson of Sausalito upon Winston’s death in 2010. After hearing the Torah’s history and learning of its connection to Kodmur’s family, Levinson graciously returned it to David Hamburger’s descendants.

Charlotte is excited about the Torah portion she will be reading at her bat mitzvah. “It is about the daughters of Zelophehad going to Moses and being very brave, so that they can ask for the land they want to inherit after their father’s death. It symbolizes women standing up for their rights,” she said.

In another twist to the story, however, Charlotte will be reading from a borrowed Torah: Yes, she will be reading from the Hamburger Torah, but it is no longer in the family’s possession. When Charlotte and her parents learned from Rabbi Jerry Levy of Tiburon, who is helping her prepare for her bat mitzvah, that his congregation at the AlmaVia senior living community in San Rafael was in need of a Torah, they decided to pass the scroll on yet again.

Last fall, on Simchat Torah, Charlotte assisted Levinson and Levy in leading services at the Torah’s dedication at AlmaVia as Jewish residents, Hamburger relatives and others looked on. “My role was to bring this precious piece of history to AlmaVia,” Charlotte said.

Levy (who confirmed Kodmur when she was a teenager living in San Diego), surmised that Hamburger saved the Torah by removing the atzei chayim, or wooden rollers. “That way, it could fit in a suitcase,” he said.Charlotte clearly grasps her great-great-grandfather’s legacy. He held on tightly to the Torah so that she could one day proudly read from it — and recognize when it was time for the scroll to serve another small Jewish community, just as it did in Fürstenau.